Dix jours après l’exécution de Louis XVI la Convention déclara la guerre contre l’Angleterre et la République Hollandaise. C’était une déclaration de fait parce que Pitt, le Premier Ministre d’Angleterre, a déjà obtenu l’autorisation du Parliament pour les dépenses concernant une guerre contre un pays qui était prêt à tuer son Roi, et en plus la République Hollandaise, située entre la France et le Rhin, faisait aussi ses préparations pour la guerre. En Mars la Convention déclara aussi la guerre contre l’Espagne.

Danton - qui sonna le tocsin et provoqua le peuple à combattre avant Valmy – partit vers l’armée dans le nord. Cette fois il portait avec lui la connaissance douloureuse que sa femme, Gabrielle, à laquelle il avait fait la cour en italien et qu’il aimait profondément encore, était gravement malade. Il arriva en Belgique, le 3 Février en demandant son annexion à la France. Le 15 Février il commença son retour à Paris. Il arriva pour trouver sa maison froide et vide, aucun feu, aucun enfant, aucune femme. Pendant son absence Gabrielle avait trouvée la mort et on avait emmené ses enfants à leur grand’mère.

Danton - qui sonna le tocsin et provoqua le peuple à combattre avant Valmy – partit vers l’armée dans le nord. Cette fois il portait avec lui la connaissance douloureuse que sa femme, Gabrielle, à laquelle il avait fait la cour en italien et qu’il aimait profondément encore, était gravement malade. Il arriva en Belgique, le 3 Février en demandant son annexion à la France. Le 15 Février il commença son retour à Paris. Il arriva pour trouver sa maison froide et vide, aucun feu, aucun enfant, aucune femme. Pendant son absence Gabrielle avait trouvée la mort et on avait emmené ses enfants à leur grand’mère.Danton alla directement au cimetière et inhuma, du sol humide et froid son cercueil, dans lequel elle avait reposé tranquillement pendant quatre jours. Il réussit à l’ouvrir pour la tenir et pour voir son visage une dernière fois. Il convoqua un sculpteur au lieu macabre et lui commanda, pas un masque de mort mais un buste de la femme inanimée. Puis il partit chez lui et trouva la lettre de Robespierre, qui disait « je vous aime plus que jamais, je vous aime jusqu’a la mort. En ce moment, je suis vous. »

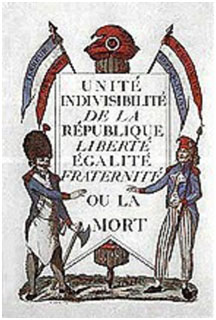

Son esprit macabre et plein des champs de bataille, son cœur ravagé par son chagrin, ses yeux distrait par les Parisiens, affamés, indigents et en pleine émeute; et ses oreilles sonnaient des nouvelles des révoltes royalistes et catholiques en provinces, Danton fit quelque chose pour laquelle, une année plus tard, il demanderait pardon au pied de la guillotine. Il persuada la Convention à remettre en vigueur le Tribunal Révolutionnaire, avec ses pouvoirs extraordinaires à faire condamner les gens à la mort. (La Convention avait licencié le premier Tribunal de la révolution avant la mort du Roi). Maintenant Robespierre parla en faveur de la demande de Danton pour le restituer et il demanda l’application de la peine de mort pour n’importe quels actes contre-révolutionnaires dirigés contre la sécurité de l’état ou de la liberté, égalité, unité et indivisibilité de la République. Une majorité des députés de la Convention s’opposèrent à la reconstitution du Tribunal. Après un long débat, la proposition fût presque abandonnée quand vers minuit, Danton se dépêcha d’aller à la Tribune. A la lumière des bougies, et parlant à voix menaçante, il avertit ses collègues épuisés qu’il n’y avait aucune alternative au Tribunal, sauf le carnage dans les rues.

Son esprit macabre et plein des champs de bataille, son cœur ravagé par son chagrin, ses yeux distrait par les Parisiens, affamés, indigents et en pleine émeute; et ses oreilles sonnaient des nouvelles des révoltes royalistes et catholiques en provinces, Danton fit quelque chose pour laquelle, une année plus tard, il demanderait pardon au pied de la guillotine. Il persuada la Convention à remettre en vigueur le Tribunal Révolutionnaire, avec ses pouvoirs extraordinaires à faire condamner les gens à la mort. (La Convention avait licencié le premier Tribunal de la révolution avant la mort du Roi). Maintenant Robespierre parla en faveur de la demande de Danton pour le restituer et il demanda l’application de la peine de mort pour n’importe quels actes contre-révolutionnaires dirigés contre la sécurité de l’état ou de la liberté, égalité, unité et indivisibilité de la République. Une majorité des députés de la Convention s’opposèrent à la reconstitution du Tribunal. Après un long débat, la proposition fût presque abandonnée quand vers minuit, Danton se dépêcha d’aller à la Tribune. A la lumière des bougies, et parlant à voix menaçante, il avertit ses collègues épuisés qu’il n’y avait aucune alternative au Tribunal, sauf le carnage dans les rues.  Ceci n’était pas un argument fort mais un argument désespéré. Pendant sa première incarnation, à l’instigation de Robespierre après le 10 Août 1792, le Tribunal n’avait rien fait pour prévenir les massacres de Septembre; Il n’y avait aucune raison pour croire qu’il aurait pu où eu la volonté de prévenir encore une fois le carnage, en exerçant ses pouvoirs extraordinaires sur la vie et la mort. Danton considérait le Tribunal comme une arme puissante dans les mains du gouvernement, le dernier espoir pour la restitution de l’ordre dans un pays anarchique et affamé, déchiré par la guerre et les conflits internes. Il n’a jamais anticipé qu’il serait utilisé contre lui, mais sur l’échafaud avant son exécution il dit, « Il y a un an j’ai proposé le Tribunal infâme par lequel nous sommes mis à mort et pour ceci je demande pardon à Dieu et à l’humanité.

Ceci n’était pas un argument fort mais un argument désespéré. Pendant sa première incarnation, à l’instigation de Robespierre après le 10 Août 1792, le Tribunal n’avait rien fait pour prévenir les massacres de Septembre; Il n’y avait aucune raison pour croire qu’il aurait pu où eu la volonté de prévenir encore une fois le carnage, en exerçant ses pouvoirs extraordinaires sur la vie et la mort. Danton considérait le Tribunal comme une arme puissante dans les mains du gouvernement, le dernier espoir pour la restitution de l’ordre dans un pays anarchique et affamé, déchiré par la guerre et les conflits internes. Il n’a jamais anticipé qu’il serait utilisé contre lui, mais sur l’échafaud avant son exécution il dit, « Il y a un an j’ai proposé le Tribunal infâme par lequel nous sommes mis à mort et pour ceci je demande pardon à Dieu et à l’humanité. Traduction : John et Christiane Preedy

Ten day’s after Louis XVI’s execution, the Convention declared war on England Ireland and the Dutch Republic. This was a pre-emptive strike, since Prime Minister Pitt had already cleared funds with parliament for war against a country prepared to murder its king, and the Dutch Republic, situated between France and the Rhine, was also preparing for war. In March war was declared on Spain also. Danton- who had rung the tocsin and roused the people to fight before Valmy – left again on mission to the army in the north, this time burdened by concern for his gravely ill wife Gabrielle, whom he had once wooed romantically in Italian and still deeply loved. He arrived in Belgium, demanding its annexation to France, on 3rd February and began the return journey to Paris on the 15th. He got back to a cold, empty house: no fir, no children and no wife. In his absence, Gabrielle had died and the children had been taken to their grandmother. Danton went straight to the graveyard and dug Gabrielle’s coffin out of the dank earth in which she had been lying for four days. He prised off the lid to hold her and see her face one last time. He summoned a sculptor to the grisly scene and commissioned not a death mask but a bust of the lifeless woman. Then he went home to the letter from Robespierre that said, “I love you more than ever, I love you unto death. At this moment I am you.”

His mind macabre and full of battlefields, his heart ravaged by grief, his eyes distracted by hungry, rioting, destitute Parisians, and his ears ringing with reports of royalist and Catholic revolt in the provinces, Danton now did something for which a year later he would beg forgiveness at the foot of the guillotine. He persuaded the Convention to revive the Revolutionary Tribunal, with it extraordinary powers to condemn people to death the Convention had disbanded the Revolution’s first extraordinary tribunal at the start of the King’s trial). Now Robespierre fully supported Danton’s call for its re-establishment and further proposed that capital punishment should be applied to counter-revolutionary acts of any kind directed “against the security of the state, or the liberty, equality, unity and indivisibility of the Republic”. A majority of the Convention deputies opposed the reconstitution of the Tribunal. After long debate, the project was nearly abandoned when, towards midnight, Danton hastened to the tribune. Speaking ominously in the candlelight, he warned his exhausted colleagues that there was no longer any alternative to the Tribunal, except a bloodbath in the streets. This was not a strong but a desperate argument. During its first incarnation the Tribunal had done nothing to prevent the September massacres; what reason was there to believe it could- or would- prevent further bloodshed by resuming its summary powers over life and death? Danton saw the Tribunal as an overwhelmingly powerful weapon in the hands of the government, the last hope for restoring order in a starving, anarchic country rent by civil strife and foreign war. He never expected it would be used against himself, but on the scaffold before his execution he said: “This time twelve month I proposed that infamous Tribunal by which we die, and for which I beg pardon of God and Man”.

Review by Rebecca Adams The Guardian http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2006/may/20/featuresreviews.guardianreview4

The Campaign for the American Reader

http://americareads.blogspot.com/2007/01/pg-69-fatal-purity.html

Dr Ruth Scurr (born 1971, London) is a British writer and historian.

She was admitted to Oxford University to read English but changed after a year to study Politics and Philosophy. She went on to study for a Master’s degree in Social and Political Theory and then completed a doctorate thesis on the political thought of the French Revolution, both at Cambridge University. After this she received a British Academy Post-doctoral Research Fellowship in the Department of Politics at Cambridge. In 1996 she spent a year in Paris at the Ecole Normale Supérieure. She began reviewing regularly for The Times and the Times Literary Supplement in 1997. Since then she has written for The Daily Telegraph, The Observer, The New Statesman, The London Review of Books, The New York Review of Books, The Nation and The New York Observer.

She was admitted to Oxford University to read English but changed after a year to study Politics and Philosophy. She went on to study for a Master’s degree in Social and Political Theory and then completed a doctorate thesis on the political thought of the French Revolution, both at Cambridge University. After this she received a British Academy Post-doctoral Research Fellowship in the Department of Politics at Cambridge. In 1996 she spent a year in Paris at the Ecole Normale Supérieure. She began reviewing regularly for The Times and the Times Literary Supplement in 1997. Since then she has written for The Daily Telegraph, The Observer, The New Statesman, The London Review of Books, The New York Review of Books, The Nation and The New York Observer.Scurr is an affiliated lecturer in the Department of Politics at Cambridge University, and Director of Studies in Social and Political Sciences for Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge where she is a Fellow. She was a judge on the Booker Prize in 2007. Since 1997 she has been married to the political theorist John Dunn.